Trigonometry in 3D Shapes Worksheets

What makes trigonometry in 3D shapes challenging for GCSE students?

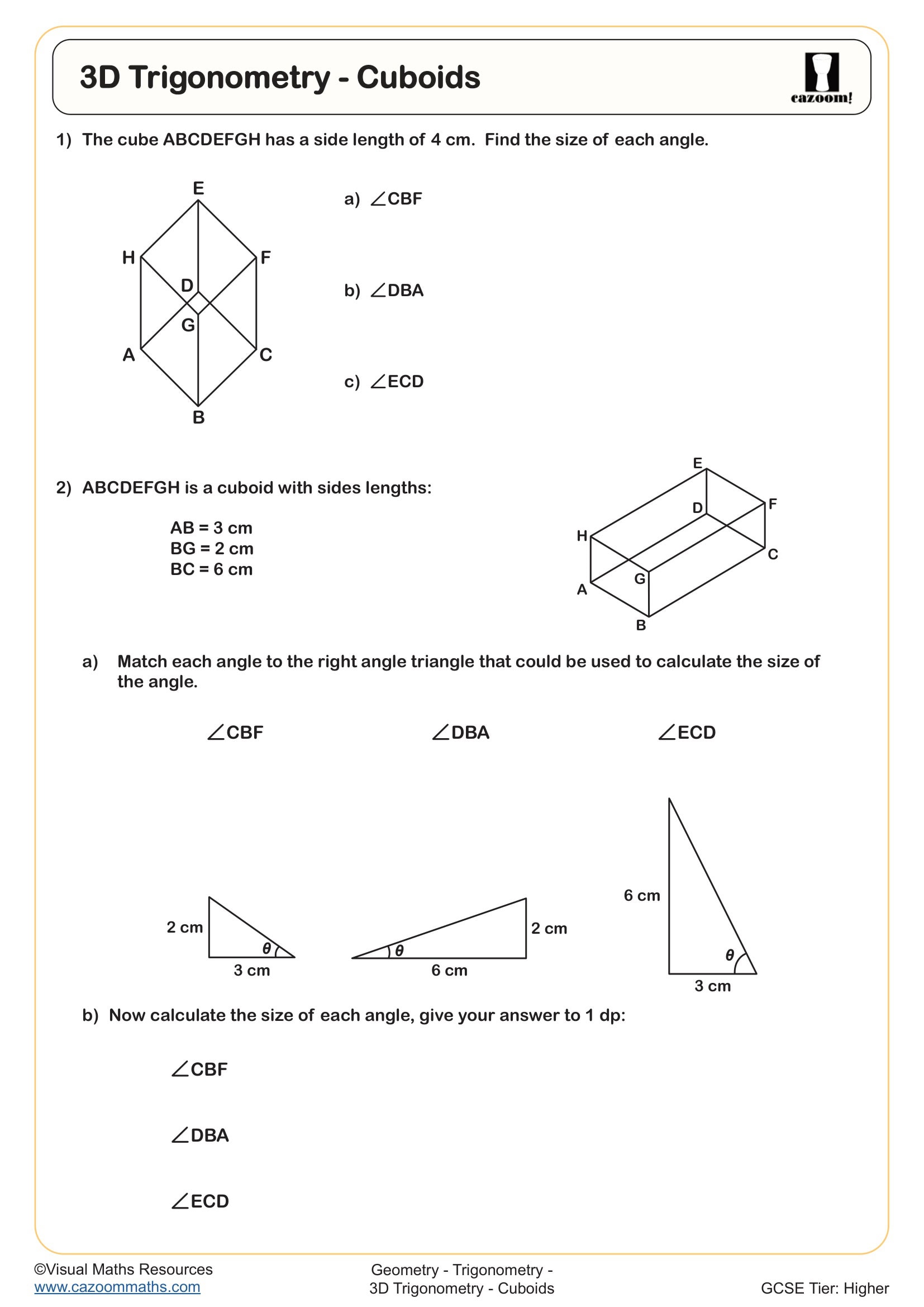

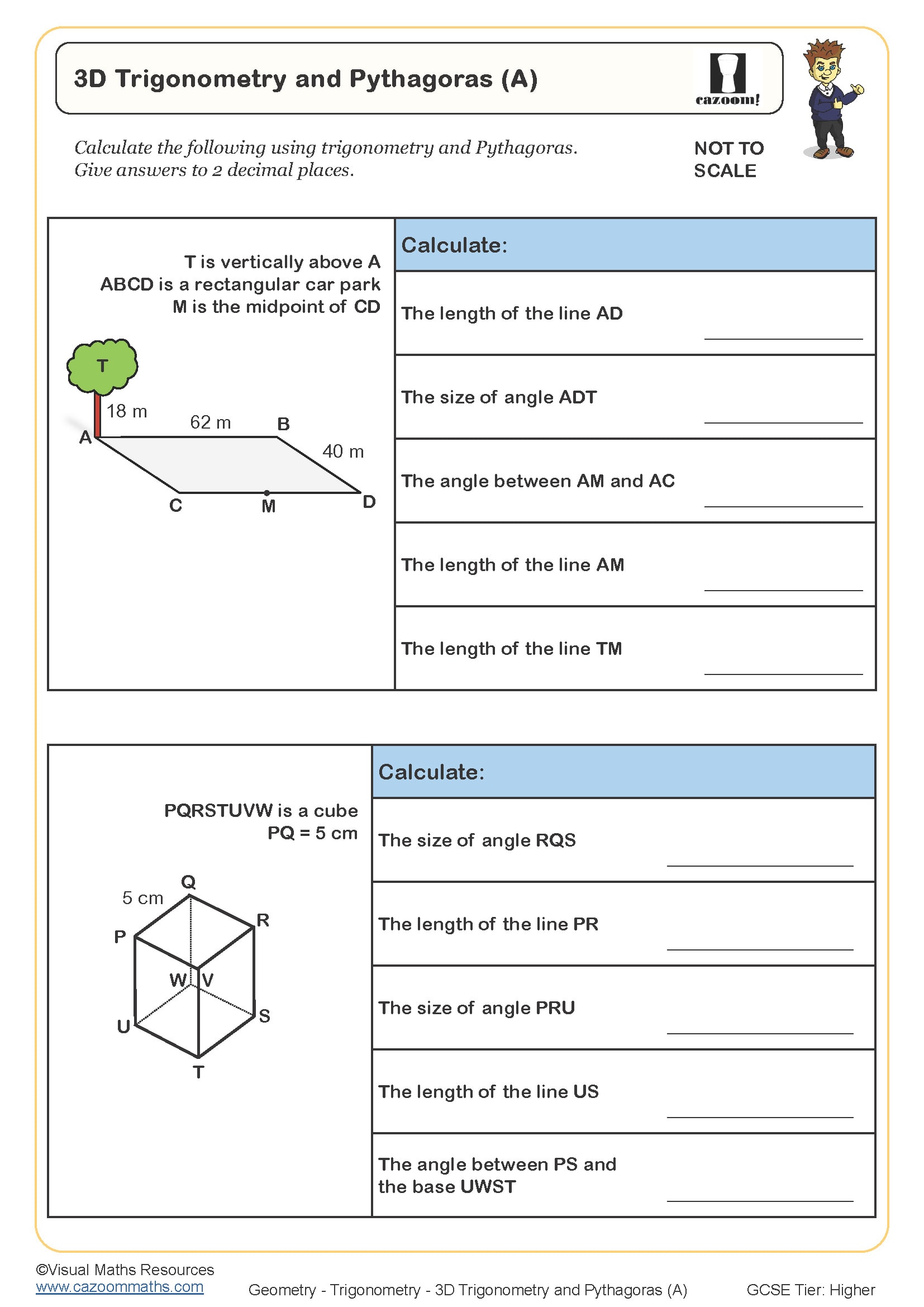

The step from 2D to 3D trigonometry requires spatial reasoning that many students find difficult. Unlike flat diagrams where the right-angled triangle is immediately visible, 3D problems demand that students mentally extract or sketch the relevant 2D triangle from within the solid shape. This visualisation skill doesn't come naturally to all learners, particularly when working from isometric or perspective drawings.

Exam mark schemes regularly show marks lost because students apply sine, cosine or tangent to measurements that don't form a right-angled triangle. A typical error involves trying to find the angle between a slant edge and the base without first calculating an intermediate length. Teachers often observe students correctly identifying which ratio to use but selecting the wrong triangle, leading to answers that seem plausible but use dimensions from different planes within the solid.

Which year groups study trigonometry in 3D shapes?

Trigonometry in 3D shapes appears in the Year 10 and Year 11 curriculum as part of the higher tier GCSE content. Students need secure knowledge of right-angled trigonometry, Pythagoras' theorem in both 2D and 3D, and properties of 3D solids before tackling this topic. The National Curriculum places it within the geometry and measures strand, typically taught after students have mastered 2D trigonometry and exact trigonometric values.

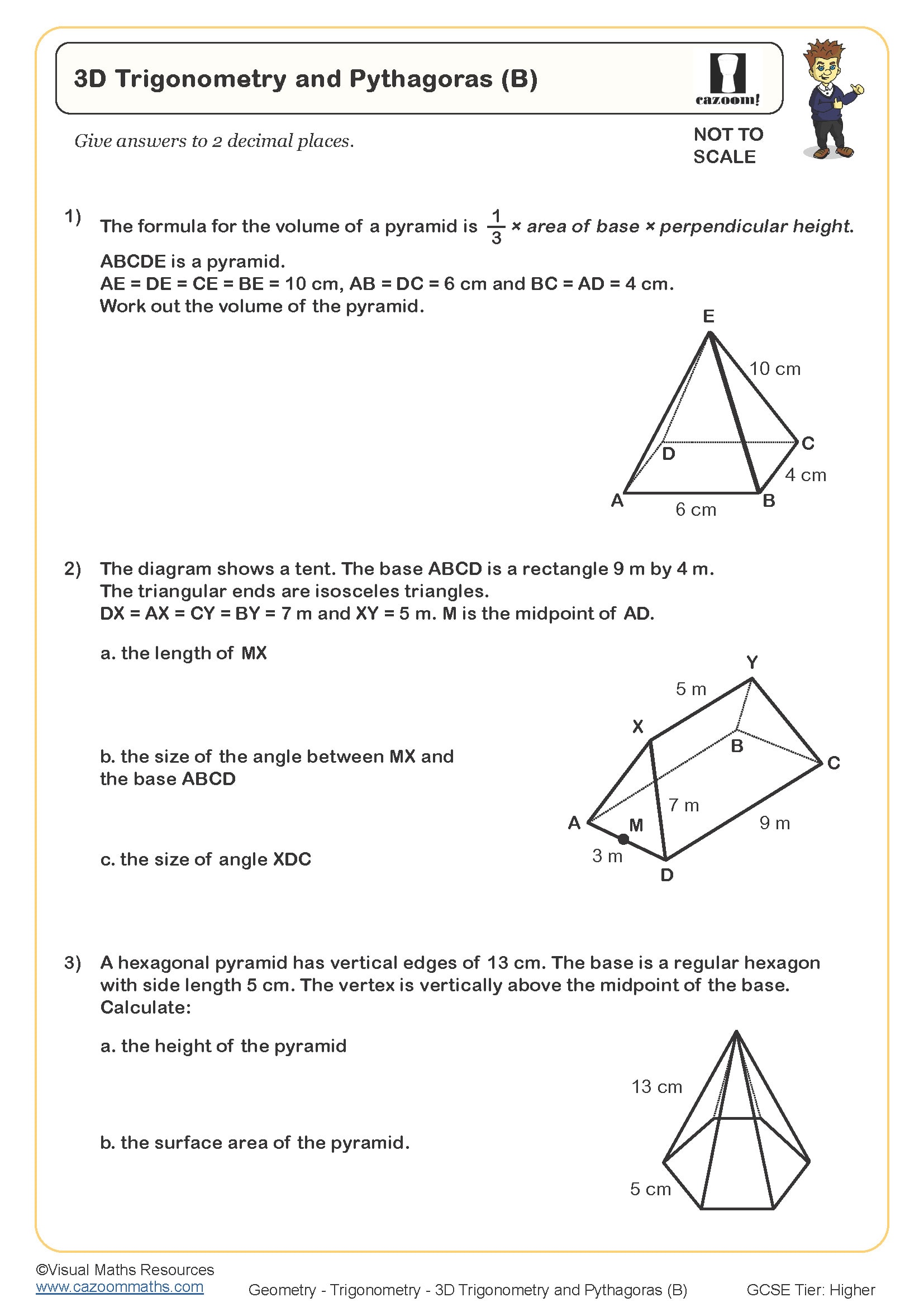

Progression across Year 10 and Year 11 moves from straightforward problems involving single calculations within cuboids or pyramids to multi-step questions requiring several stages of working. Year 11 students encounter problems embedded within GCSE-style contexts, where identifying the correct approach becomes part of the challenge. Questions may combine trigonometry with volume, surface area, or bearings, testing whether students can select appropriate techniques from across the specification.

How do you find the angle between a line and a plane?

Finding the angle between a line and a plane involves identifying where a perpendicular from one end of the line meets the plane, creating a right-angled triangle. Students draw this triangle by marking the vertical height, the horizontal distance along the base, and the slant line whose angle they're finding. The angle of elevation or depression between line and plane sits at the base of this triangle, calculated using the tangent ratio (opposite over adjacent) or another appropriate trigonometric function.

This skill appears in practical contexts across engineering and architecture, particularly when calculating roof pitches, ramp gradients, or sight lines in stadium design. Structural engineers use these calculations to determine load distributions in frameworks where supporting struts meet horizontal beams at specific angles. Understanding these angles proves essential in construction planning, where building regulations specify maximum gradients for accessibility ramps or minimum roof pitches for drainage, all derived from trigonometric relationships within three-dimensional structures.

How should teachers use these trigonometry in 3D shapes worksheets?

The worksheets scaffold learning by presenting problems in increasing complexity, starting with clear diagrams and explicit instructions before moving to questions where students must decide their own approach. Many include diagrams that require annotation or additional construction lines, encouraging students to develop the habit of breaking 3D problems into manageable 2D components. This structured progression helps build confidence before students face less guided exam-style questions.

These resources work effectively for targeted intervention with students who understand 2D trigonometry but haven't yet made the conceptual leap to three dimensions. Teachers often use them during revision sessions in Year 11, where small groups can discuss their approaches before attempting individual questions. The answer sheets support independent homework, allowing students to self-assess and identify specific areas needing clarification. Paired work proves particularly valuable, as verbalising which triangle to use often reveals misunderstandings that silent individual practice might miss.